If you prefer reading, instead of listening, scroll down:

I married my husband twice. The first time, we eloped on a sandy beach in Hawaii.

The second time was a real Italian wedding with family and friends in the hills of Sant’Andrea a Morgiano, in Tuscany, a place that’s always meant a lot to me.

When I was looking for a villa to host our wedding, I walked by a beautiful old farmhouse that I thought could be perfect. The name above the door read, Fattoria La Nutrice. To find out who owned the place, I asked my great-aunt, the pharmacist in Antella. She knew everyone! She gave me Paolo Zorzet’s number.

When Paolo gave me a tour, I fell in love with the place. The old stone walls, the sundial and citrus trees in terracotta pots.

I asked him for the story of the farmhouse, he told me that during the Renaissance, it was where wealthy families entrusted their newborns to wet nurses for the first 18 months of their lives. One of those newborns was Ginevra de’Benci, that according to a local historian, was the famous model for Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

The idea that the place where I was standing, in the hills that I love, was connected to Leonardo Da Vinci and the most famous painting in the world, got me interested. I had to know more!

The story starts in the year 1457 at Villa Il Poggio, a magnificent villa that still stands on top of a nearby hill. In that year, a daughter, Ginevra, was born to Amerigo Benci, the director of all the Medici banks in Europe. Amerigo named his daughter after the juniper bushes that still surround the villa, but everyone called her Bencina as she was the youngest in the family.

Juniper is widely used in Tuscan cooking, as well as to make gin. My mother used to put the tiny dark-blue berries in her wild boar stew, one of my favorite dishes as I was growing up. But don’t eat the berries! I’ll never forget the sharp, unpleasant taste when I bit into one by mistake.

That stew became my ‘expat’ dish—the taste of home while I was away. My mom would seal it in a mason jar, pack it in her suitcase, and bring it to me in France when she visited. I haven’t eaten it since I became a vegetarian, but I will always remember the delicious taste of wild boar flavored with juniper.

But back to the story!

Ginevra was christened in the parish church of San Donatino a Campignalla, a tiny eleventh-century stone building surrounded by olive trees, only a few minutes away from the villa. The priest came up from Antella, the village where I was born, to baptize her and wrote her name in the record book.

I was christened in the chapel across the hill. According to my mother, I was teething and chewed through the prayer book.

The church where Ginevra was christened now belongs to Paolo, the owner of Fattoria la Nutrice. He suggested that my husband and I get married in that church. But when I asked the priest, he refused to officiate over our marriage, saying, “this is a sacred place, not an amusement park.” He has every right to be tired of so many foreigners coming to Tuscany to get married!

Leonardo da Vinci was born in 1452 in Vinci, Tuscany, the illegitimate son of Ser Piero, a notary, and a woman named Caterina, about whom we know nothing.

Leonardo’s father, moved to Florence . Wanting to find an occupation for his teenage son, he introduced him to Andrea del Verrocchio, the famous painter and sculptor, and persuaded him to take him on as an apprentice.

Ginevra’s father, Amerigo Benci, was an art lover, who often visited Verrocchio’s workshop. He invited the young Leonardo to visit him in his building, which is surely when Leonardo first met Ginevra, who was five years younger than him.

Normally, the daughters of powerful Florentine families weren’t allowed to meet with young men outside their households. But in her father’s building, Ginevra was surrounded by the young talented artists her father welcomed into his home.

At that time, wealthy Florentines spent the summer in their countryside villas, to escape the heat of the city. The story is that Ginevra and Leonardo spent summers walking together through the hills of Sant’Andrea a Morgiano. I’ve often walked those hills myself, as someone who finds peace among the olive trees and in the oak woods.

Then in 1474, when Ginevra was only 16, her father forced her to marry Luigi Niccolini, a man 15 years older. Her father was one of the most powerful men in Europe, so of course she could never have married Leonardo da Vinci, an artist and a bastard.

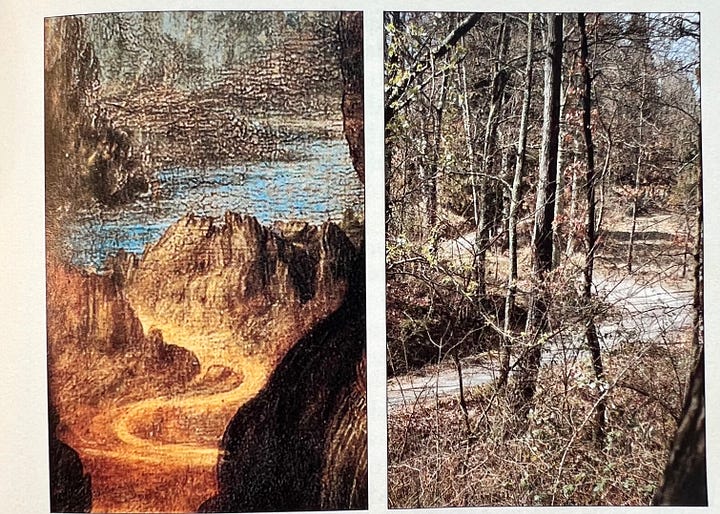

That same year, Leonardo painted “Ginevra de’Benci,” a beautiful painting now in the National Gallery in Washington DC. It shows her in 3/4 pose, looking sad and surrounded by juniper bushes. In the background are the hills where they spent so much time together, and the city of Florence.

The Florence that Leonardo painted now looks different — the Dome was built later, and the San Pier Maggiore tower was demolished in the 18th century by the Grand Duke of Tuscany because unstable — but I recognize that view. I see it myself whenever I walk on the dirt road that winds up that hill. I cross the oak wood and the little stream, then walk up the hill through the olive trees, and I imagine Leonardo and Ginevra walking with me, so many years ago.

It’s also the first place I went walking in Tuscany with the Canadian man I met in my Thursday evening rock climbing class in Grenoble, France. He took a picture of me that evening in the olive grove beside the Fattoria La Nutrice. Three years later, I married that man under an old fig tree in the garden of Fattoria la Nutrice on a hot July evening.

Leonardo’s painting is a bit of a mystery. It wasn’t commissioned. In those days every artwork was commissioned. The buyer signed a contract in front of a notary. A delivery date was established, and the client had the right to go and see the work as it progressed.

None of that happened with Leonardo’s painting of Ginevra de’Benci. He kept the painting with him for years, before finally donating it to Ginevra’s brother.

All of that led the local historian Massimo Casprini to conclude that Leonardo painted it for himself, out of his love of Ginevra.

Once Ginevra was married, there were few chances for her to spend time with Leonardo. She was in an unhappy, childless marriage. Things were also difficult for him.

In 1476 he was accused of having a relationship with a young man, said to be a prostitute, who used to work in Verrocchio workshop. The charges were made anonymously, by leaving a letter in the so-called tamburo in the Palazzo Vecchio. The tamburo was a small opening in the wall to allow anyone to make anonymous accusations.

The trial took place on April 9th 1476. Leonardo was acquitted. But his name had been tarnished, and Lorenzo de Medici, the ruler of the Florentine Republic, asked Leonardo to go to Milan, to work for Ludovico Sforza.

It was in Milan, exactly 30 years after painting “Ginevra de’Benci,” that Leonardo began a new painting of Ginevra. Once again, nobody commissioned this painting. This is the painting that the world knows as the ‘Mona Lisa,’ even though Leonardo himself never gave the painting a name.

The painting shows Ginevra as a mature beauty in three-quarters view, turned to the left, mirroring the previous portrait. The landscape behind her includes the road down to the juniper ravine where they used to spend time together. It’s one of the few places that is cool when summers are hot.

In 1517, Leonardo left for France, taking the Mona Lisa with him. He knew that after his death the painting would end up in the hands of some merchant, so he sold it himself to Francis I, the King of France.

All through his career, Leonardo wrote copious notes about his work and his studies. But he never wrote a word about the Mona Lisa, and he never spoke to anyone of the woman’s identity.

While I like to think that the woman in the Mona Lisa is Ginevra, it’s not something that has ever been proven. Thirty years after Leonardo’s death, the historian Vasari wrote in his biography of Leonardo that the subject of the painting was Lisa Giocondo, or Monna Lisa, but he provided no evidence of this.

More recent studies have found letters that Leonardo drew in the woman’s pupils with a small brush.

The letters in the right pupil are L V (for Leonardo da Vinci). On the left pupil is a single letter, B. I like to think it’s for Bencina, Ginevra’s nickname.

We may never know what really happened in the hills of Sant’Andrea a Morgiano in that corner of the Tuscan countryside all those years ago. But the places where Leonardo and Ginevra walked are still there: Villa il Poggio, the parish church, Fattoria la Nutrice, the olive groves, and the oak forests. For me, knowing the story of Leonardo and Ginevra fills those places with new meaning and beauty.

References:

Massimo Casprini, La Gioconda. Il mistero dell’identità svelato da una storia d’amore, 2017 EChianti.

Mona Lisa and Me